![]()

Recently I have had the extreme pleasure of spending some most enjoyable hours reading the memoirs of a woman who was raised aboard sailing vessels in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Her maiden name was Young, but she writes under the name Elizabeth Linklater, her married name. Imagine my surprise when I came upon the section where she describes in great detail her experiences in Portland during the Christmas season of 1889 and on into mid February of 1890. A year or so ago I had blogged about an 1889 Oregonian article describing Christmas aboard the various vessels in port. This was before I had discovered this book. The article tells of the cozy Christmas with Captain Young, his lovely wife, and two daughters, aboard the full-rigged, Orpheus, and how they made plum duff for the crew. In this book the interview by the Oregonian reporter is mentioned, and Elizabeth remembered, after many decades, the opening lines: "A pleasant home is that on board the Greenock ship Orpheus. Captain Young is accompanied by his wife, a comely British matron."

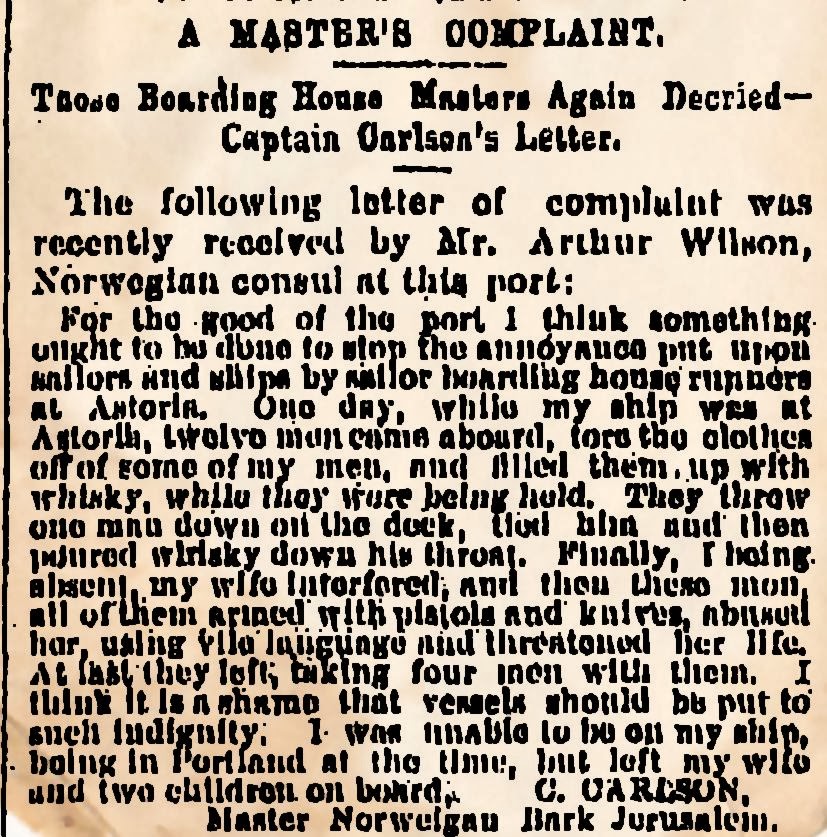

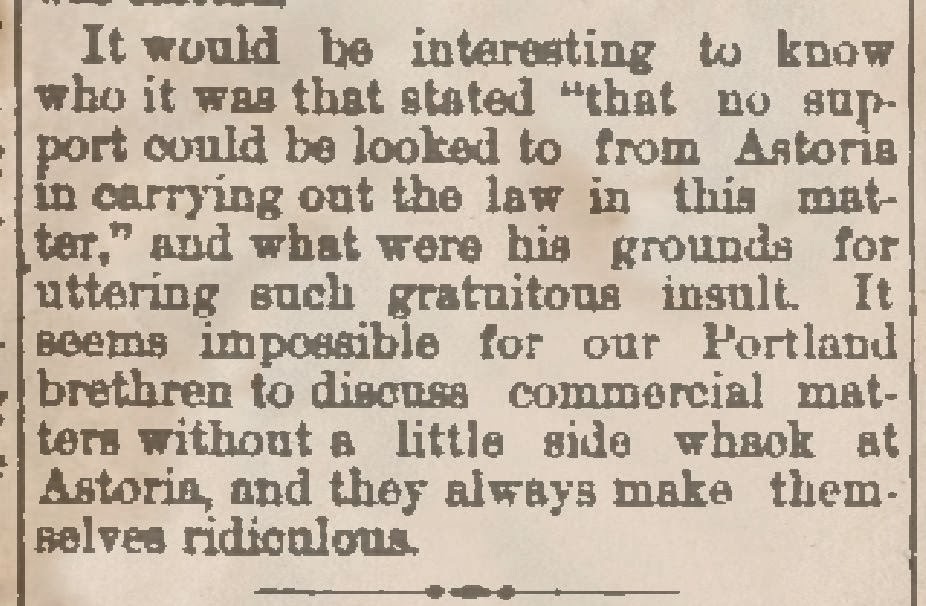

I found this to be a very important book as far as my insights into the crimping and shanghaiing in Portland and Astoria at the time. Elizabeth had been in Portland before aboard the Narwal, in 1876. The visit had been uneventful except for the desertion of the crew and some dealings with Jim Turk for replacements. However, the second visit, in 1889 was a turning point in the life of the two ports. Jim Turk was losing his control of the business, The Astoria sailor’s boarding houses of Dee and McCarron, the Grant Brothers, and Larry Sullivan were vying for the upper hand. It was a bad time for Jim Turk: while the Orpheus was in the harbor Jim’s wife, Kate, died in St. Mary’s hospital in Astoria and was buried in the frozen ground at Portland's Lone Fir Cemetery.

It was also a very bad time to visit the port, as you will see in the passages I will put in this blog. There is also much written about the battle of the crimps in the newspapers of the time. The Portland Board of Trade had just raked Jim Turk over the coals and had asked the U.S. Commissioner to establish a special U.S. Marshal to guard the crews to make sure they made it to sea, and were not stolen by Astoria crimps. It was too little too late as far as law enforcement was concerned. The Astoria crimps went so far as to have the U.S. Marshal, a man named Fitzsimmons, arrested for pulling a gun on them—as incredible as this may seem.

It is fascinating to read Elizabeth Linklater’s account as a very observant girl in her teens, then to read the Daily Astorian and Oregonianaccounts of the same incidents. All this I had hoped I could put in my upcoming book, The Oregon Shanghaiers: Columbia River Crimping from Astoria to Portland, but the story was edged out by more necessary things. That is what blogs are for—at least, that is what this blog is for—all the things that won’t fit in my books. I noticed that A Child Under Sail, though out of print, is still available in many used bookstores around the globe. I strongly suggest that any lover of true sea stories buy themselves a copy. I found that the observant young Elizabeth had gone into detail on things that most other yarn spinners neglected to mention. She is especially good about describing the deterioration of food stores in the months at sea.

Incidentally, the man she refers to as “young Jim Turk” was Charles Turk, Jim’s eldest son who managed the Astoria house. She is about 110 miles off when she says that Portland is 200 miles upstream.

Here is Elizabeth Linklater's account of coming to Portland in the snowy winter of 1889:

The Orpheus Visits Oregon (From A Child Under Sail)

On December 15th we sighted the lights on Tillamook Head and Cape Hancock, but with a strong south-east wind we had to stand off shore. On the morning of the 16th we tacked for shore again, but with the wind increasing to gale force and the barometer falling to 29'50 at three p.m., we again stood to sea. At six-thirty p.m. the wind shifted suddenly to the north-west and became almost a calm. We again saw the lights on Tillamook Head and Cape Hancock. On Tuesday the 17th we got a pilot and a tug-boat, and crossed the bar without difficulty, the breakers on either side looking very magnificent. We anchored off Astoria quite close to the shore. The welcome we received at the Consul's, in the custom house, and from our own agent seemed overwhelming after meeting no one except our own ship's company for so long. In comfortable chairs, set before huge fires, we sat and talked, and were talked to, as friends of long standing.

Later we towed up the Columbia river with the tug Willamette Chief, a stern wheeler, lashed to our port side. A very curious tug boat she appeared. As one of the men said, 'She looked like a ware-house tied on to us.' The captain invited us into his wheel-house, where we sat in warmth and comfort to enjoy the beauties of the river scenery. There was a good fire in the stove, and I expect the tea he gave us was even more appreciated than the view, fine though the latter was. (I talk a lot about food, but those who have never known a sailor's life have never known the joy of a fresh mess after months of salt and tinned foods.) The following day we again went on board the tug boat, and had dinner there.

![]() |

| Willamette Chief |

It is two hundred miles from Astoria to Portland, and I was very sorry it was not more. We made fast in Montgomery Dock on the Albina side of the river, the opposite side to Portland. It is hard to realize, in these days of air mails and wireless, that our last home news had been written in the middle of August, and this was the middle of December; so we were very anxious to get ashore for letters.

As Christmas was so near the shops were all decorated, but the only one I remember vividly is that of the butcher who supplied us with meat. I counted sixty half-bullocks hanging round the walls, and over a hundred sheep, besides calves and pigs and poultry and sucking-pigs; and everything was ornamented in colours and decorated with patterns cut on the skin. Some of the sheep had the Stars and Stripes painted on them, and little tufts of wool, left at the tip of their tails, had' been washed and combed. The butcher was so gratified by our appreciation of his artistic decorations that he sent us a turkey and a sucking-pig for a Christmas present. Two other trades people also sent us turkeys, and another plum-puddings, so the season was well celebrated as far as food was concerned. The surroundings, too, were of the old, fashioned Christmas card appearance. The ground ' was covered with snow, there was hard frost, and bright sunshine. We went to church in Portland on Christmas Day-a lovely church, beautifully decorated, and very warm and comfortable, where we were given a hearty welcome and made to feel that, wayfarers though we were, there was one bond that held us all.

![]()

We had to cross from Albina to Portland by ferry, and we were chartered to load grain at an elevator very near to the landing-stage from which it left. But then we were re-chartered to load flour at a mill two miles down the river, still on the Albina side, where no boat called. The only way of getting from there to Portland was by first walking to Albina, either by a road which went a long way round and in wet weather was almost impassable, or by walking part of the way along a railway track from the flour mill. This was a single line built on trestles raised thirty feet from the ground. At regular intervals there were logs jutting out from the sides, and should one meet a train, and the engine fail to stop, one had three choices: of being run over, of hanging on to one of the logs, or of jumping down thirty feet. But after a few days we discovered that if we told them at the mill that we were going along the track, they would telephone to the other end and stop the train, should it be ready to start. On one occasion when walking along the track, with snow falling and lying thick on the trestles, my mother slipped through what must have been a broken plank. Luckily it was not a big enough hole to let her right through, but held her at the waist. She had an umbrella open, and her appearance convulsed my father and me to such an extent that we had great difficulty in pulling her out. But it was not as amusing to her as it was to us.

![]() |

| Portland Flouring Mills |

About New Year time some of the crew went ashore to celebrate, and walking back late at night along the trestles, one of their number fell to earth unnoticed. He was not missed till next morning, when he reappeared none the worse for his fall. He had slept in the snow. There were river boats that passed the mill several times a day, and if we happened to be in Portland when one was leaving, it would put us alongside our ship; or if we saw one going up the river in time to hail it, it would stop for us. But there was no way of getting on board at night, unless by walking many miles, so we were as closely tied to the ship in the evening as if we had been at sea.

The purpose of our re-chartering was that we should take a cargo intended for the Clan Mackenzie, which had been run down and sunk in the river. She was being towed up by the Oklahoma, and had anchored for the night a little below Coffin Rock, an old Indian burying ground. The Oregonian, bound for San Francisco, ran right into her bows, killing two men and seriously injuring two others. She sank almost at once. The captain's wife and a child seventeen months old were on board. They were rescued and taken on board the tug. The Oregonian was so much injured she had to return to Portland. The captain of the Clan saved nothing but his chronometers. The tug boat captain had his wife and family with him taking them home after spending Christmas at Astoria, and they took the captain of the Clan, and his wife and child, to stay at their home. That voyage of the Clan Mackenzie had been a bitter experience for all on board. They were one hundred and sixty-nine days on the passage from Rio de Janeiro, they had been driven back round the Horn three times, and then they experienced this disaster when they thought themselves out of all danger.

I had looked forward to the ship's being moored to a wharf, and the attendant joy of going ashore when I wanted to; but now, with such difficulties to be faced after getting on land, I had few of my expected pleasures except the stillness of the ship. There was little chance of visiting or having visitors. The only habitation anywhere near us was a little log hut in which a Scotsman and his wife were living. They had been in Canada for many years before settling in Oregon. Mrs. Cameron spoke to us one day as we were passing, and asked us to go in and have a cup of tea; and afterwards we often stopped on the way from Albina to the mill and had tea with her. She also gave us strawberries and raspberries of her own canning.

Two reporters interviewed us at Albina, and a paragraph in the newspaper Oregonian began: 'A pleasant home is that on board the Greenock ship Orpheus. Captain Young is accompanied by his wife, a comely British matron.' I well remember how, as a small child, I loved the American newspapers that we got from Yankee shops, for even then they had usually a children's section.

The New Year was brought in by the ship's bell being furiously rung, and the crew coming aft to serenade us. They assembled at the cabin door with a band consisting of an accordion, a whistle, a drum and triangle. The accordion and the whistle were not on the best of terms, and when the men asked me to start 'Auld Lang Syne,' I could not decide which instrument to follow; so I suggested it might be better if I began alone. We gave them all drinks and cake, shook hands with them, and exchanged good wishes. They were all sober but in high spirits, though one would have thought there was little to cheer them in their present surroundings, except that they had each had half a chicken for dinner, followed by plum-duff. Only a few men went ashore, and only one came aboard drunk. He came straight aft and asked for his discharge. He was told to come back next morning, but by then he had changed his mind.

More and more snow fell, and the weather got colder and colder. All the ports in my room were coated inside with ice, and in the morning I had to break the ice in the water-jug. Father bought a new stove for the after-cabin, a very neat little thing with two removable rings on top, on which we could boil a kettle and make tea for ourselves. The galley fire went out after six o'clock, and nothing hot was served later than that. It must have been the comfort brought by the new stove that kept us aboard, for we decided to wait till the weather was better before trying the trestle journey again. One morning, however, as there was no sign of the cold lessening, we wrapped ourselves up well and started for Portland. When we got to the railway track we found a stationary train on it, and we had to edge along the line holding to the sides of the trucks. I would gladly have given up all thought of going to Portland, but my mother, who was never daunted by any obstacle, laughed at me, and I did not fall off as I had expected. The streets in Portland were full of sleighs, and I longed for a ride, but the charge for hiring one was five dollars an hour.

We had hoped to get back to the ship by a river boat, but there was none running, so we had to return as we had come. It was bad enough walking in the morning, but it was. much worse by the afternoon, as a strong wind had risen that blew the still falling snow in our faces. We could scarcely open eyes or mouth. The snow had drifted badly, and we kept sinking to our knees in it. But the walk along the railway track was the worst part of the journey. It was quite terrifying, and several times we feared we should be blown off. After that expedition we stayed on board for a few days. The officers had some good days shooting wild duck; and one wild goose might have graced the cabin table had it not fallen in the water and been lost.

We finished loading on January I6th, and left for Astoria, towed by the Oklahoma. Snow was falling, and thick weather made it necessary to anchor very soon after leaving. The captain of the tug boat brought his steward on board to entertain us with musical selections on a mouth-organ and guitar, which he played simultaneously, the mouth-organ being fastened round his neck by a wire. It was an amusing performance. We would have enjoyed it however badly he had played, but they were good instruments, and he played them well. Stringed instruments were seldom seen in a ship's fo'c'sle, for rapid change of climate and the difficulty of getting new strings made it impossible to keep them in order. An accordion or a concertina was much more suitable.

We towed past the sunken Clan Mackenzie. A wrecker from San Francisco had the contract to raise her, and after he had the water nearly all pumped out, a shovel that had been left in the hold got into the suction pipe, burst it, and she filled again. When we passed her the hole in her bows had been patched below the waterline, but above it we could see right into her fo'c'sle. We spent most of the time in the wheel-house of the tug, as we had done on the way up the river. Wintry weather had made the scenery still more beautiful.

![]()

We anchored at Astoria on the 19th, very near shore, but not alongside a wharf. In this case, however, Providence was kind in surrounding us with water. Had we been moored at a wharf the events that followed would have been much more alarming. The Columbia river was not deep enough for the Orpheus to come down fully loaded, so the remainder of the cargo came down by lighter and was all on board by the 23rd. Then Father went up to Portland to clear the ship at the customs house, and to get some sailors in place of those who had deserted. There was keen competition between the boarding-masters in Portland and Astoria as to who would get the job of supplying men. To begin with, their habit was to entice the men away from their ships by filling them with drink. Then they kept them under the influence of drink till they could be put on board a homeward bounder. The boarding-masters got two months' advance of wages for each man, giving him in return a very

few clothes, a donkey's breakfast, [A mattress stuffed with straw.] and a blanket. In one case when a man complained to the boarding master that he had no blanket, the latter took a blanket from another man, tore it in two, and gave a half to each. Generally the stolen men had been six or eight months in the ship they were taken from, and all the money they had earned during that time was lost to them. Their clothes were left behind, and the pay they earned on their new ship went on the two months' advance to the boarding master, and on supplies from the slop-chest that were absolutely necessary to them in their unclad state. They were usually penniless when they got home.

There was a great scarcity of sailors in Portland at that time, but Jim Turk, a boarding-master of world-wide fame, arranged to supply us with five. The boarding-masters who had been unsuccessful in getting my father's business in Portland wired to those in Astoria, and when Father got there on Saturday night, two or three of their number and a gang of ruffians were waiting for him. They demanded to know when the men he had shipped were coming down. He refused to tell them. Thereupon one of them showed him a telegram that said, 'Arrest captain of Orpheus.' This was for shipping two men who had run away from the Arthurstone. It was against the law to engage men from another ship if she was still in port; but both these ships had left. Father managed to get clear of the boarding masters, and aboard his own ship. He had arranged for the men to come to Astoria in charge of a United States deputy marshal and young Jim Turk. The crowd on the wharf waited for their arrival and a fight began"

![]() |

| Charles Turk |

The Astoria men tried to kidnap the sailors, and succeeded in getting one. A steam launch was waiting and the marshal and young Turk managed to get the other four sailors into it, but not before their faces were badly cut and bruised and covered with blood. After getting washed and patched up, Turk went ashore to bring the sheriff off. But the crowd turned on him again, and he had to retreat. Then the captain of the launch went ashore, but did not return, and at last our own boat was sent, and succeeded in bringing off the sheriff. He said the leaders of the attack would be severely punished for assaulting a U.S. marshal; but trouble of that kind was so common that I expect no more was heard of it. On a previous voyage to Astoria my father had complained to someone in authority about the boarding-masters who infested his ship, trying to get his men, and was told, 'Order them ashore, and if they don't go, shoot them!' We had to get a night watchman from the shore, lest the men should be stolen again, and the next day Father had to make a statement regarding the desertion of the man who had been kidnapped, and who had subsequently been lodged in prison. The U.S. marshal was arrested on a charge of assault and battery as he was leaving for Portland, and had to find bail for fifty dollars. This was done to prevent his getting to Portland, and lodging a charge against the boarding masters; the chief of police in Astoria being, it was thought, in league with them. We went ashore next day, and had a very disturbing time. We had shopping to do, our last chance for several months to come, and Father was very busy with the ship's affairs. Boarding masters and their runners followed him wherever he went, and when we all met in the stevedore's office, several of them passed and re-passed the windows, peering in with vindictive looks. I quite expected them to shoot him. The thaw had begun, and the wooden streets that had been so thickly covered with snow were in a dreadful mess. This was one of the few occasions on which we thought of our ship as a blessed sanctuary.

Next morning, January 28th, we towed as far as Sand Island and anchored there. The weather was much too stormy to cross the bar. The deserters' clothes were sent ashore, and when the rest of the crew saw that, they came aft in a body to complain about going to sea a man short. They also said that the four men newly shipped were no sailors. They were perfectly right in this, but there were no better to be got. One man, who had been signed on as A.B. at £6 a month, had never been to sea before. Another, who had been in a small coast sailing craft, looked aloft, and said, 'I might go up there in daylight, but never at night.' Another was a very old man, so dirty that the men in the fo'c'sle refused to let him sleep there-they said they could sweep the fleas up in a shovel after he came aboard and put him, with straw for a bed, in the disused side of the pigsty. He was decidedly half-witted, and couldn't even remember to come up the ladder on the lee side of the poop, though the dog Juno knew what he should do, and chased him down when he approached the weather side.

It was exasperating not to get right away to sea, but at least our fear of boarding-masters had been removed. We were now too far away for them to be revenged on us. They ruled Astoria, where everyone was afraid of them. The sheriff, when he was brought on board, asked the deputy marshal why he hadn't shot two or three of them; but they had managed to snatch away his revolver at the very beginning of the fray.

It was as well for our peace of mind when we left Astoria that we did not know how long it would be before we crossed the bar. We waited at Sand Island from January 28th, till February 16th, and all that time the bar was impassable. That was an experience which tried the patience of all on board.

Gale succeeded gale, and while we considered ourselves in safety it was discovered that an anchor had gone, and we were dragging the other, and drifting on to Sand Island. The spare anchor had to be got out, and that was no easy matter. A tug boat lay near us, hoping for salvage. Twice the bar boat came off with orders to get steam up and be in readiness to heave up the anchor should he report the bar smooth enough to cross; but returned to say the risk was too great. The ebb tide ran down like a sluice. The thaw had' continued, and snow melting on the hills flooded all the lower part of Portland. The ships in dock there were in danger. One, the Alameda, was made fast to the piles supporting the dock she was lying at, and the piles broke loose, and they had to get more ropes and make her fast through her ports and right round the warehouse. A whole furniture factory came down the river and stuck against a bridge. Some of the furniture was got out, but a lot floated away to sea.

Many logs of wood floated past us, and some were got on board. One huge one was very difficult to handle, but it was well worth the trouble. It was so big the carpenter said it would make a mizen topmast. This success fired their enthusiasm to such an extent that when the tide slackened the second mate, the carpenter, and the boys took the boat to Sand Island, and got more spars that had been washed up there. They also dug up a small tree, which we planted in a cut-down pork barrel. The mails had been held up owing to snow on the railway lines, and we had had no letters for a long time, but luckily they got through before we left. The bar boat brought them off, and they were thrown on board tied to a piece of wood that was attached to a line. Our letters for posting were sent back in the same way.

All things come to an end, even gales of wind, and on February 16th the bar was reported smooth enough to cross. The donkey-fire was lighted, the anchors hove up, and we were soon over, and the long passage home was begun. We got a good slant, and ran right into fine weather. Good temper prevailed both fore and aft. Conditions in Portland had not made our stay there attractive, and now we were homeward bound. Even the Horn, going from west to east, was not worth worrying about.

(Next post: The same incident from the view of the newspapers)